HINfluence

Thought Leadership Blog. Click a post title below to open it.

Using Data to Illustrate Health Disparities

MiHIN recognized Black History Month and reflected upon what it means to support our ecosystems’ commitment to advance race equality and implement our work with an eye toward health equity.

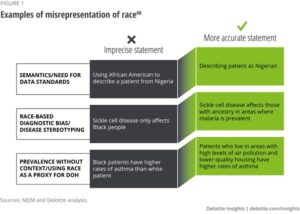

On a systemic level, data on race and ethnicity is critical to understanding who patients are and how to improve their care, as well as identifying the root causes of health disparities. Health information exchange is critical data infrastructure to collect race and ethnicity data in order to fully understand, challenge and overcome racial inequities that persist within our society.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, “how we ask for, analyze, and report information on race and ethnicity affects our ability to understand the racial and ethnic composition of our nation’s population and our ability to identify and address racial disparities in health and health care. The accuracy and precision of such data has important implications for identifying needs and directing resources and efforts to address those needs.”

Progress is being made. Last month, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) announced its proposal for updating the standards used for collecting race and ethnicity data

A Working Group made up of representatives from government agencies that collect or use race and ethnicity data presented the following recommendations:

1. Collect race and ethnicity data in a single question

The Working Group found that the separation of race and ethnicity questions is confusing to many respondents who view both race and ethnicity as similar concepts.

2. Add “Middle Eastern or North African” as a new category

The Working Group found that persons from counties in the Middle East or North Africa (MENA), who are currently in the “White” race category, do not share the same experience as persons with European ancestry who are included in this category. A MENA category would include individuals who identify with nationalities and ethnic groups with origins in countries including but not limited to Lebanon, Iran, Egypt, Syria, Morocco, and Israel.

3. Require detailed collection of race and ethnicity categories

The Working Group found that agencies collecting race and ethnicity data should collect data at a more granular level such as by country of origin.

Accurate and timely data is imperative for advancing health equity, and our ability to identify and address racial disparities within the care ecosystem hinges on our understanding of the racial and ethnic composition of our nation’s population. Updates and inputs to federal race and ethnicity reporting are an important step in the right direction.

The OMB is seeking feedback on its recommendations through a public comment process. Comments on the proposals are due by April 12, 2023.

From the Desk of Shreya Patel-HHS & SAMHSA Proposed Rule Update from MiHIN

On November 28, 2022 the Health and Human Services Department (HHS) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) released a proposed rule for 42 CFR Part 2 information (Part 2 Information).

Part 2 information is information that comes from a facility regulated by 42 CFR Part 2 and is federally defined as an entity that 1. Receives federal funding and 2. Holds itself out as an entity primarily concerned with the treatment of substance use disorders.

The proposed rule would increase care coordination for treatment purposes, aligning Part 2 sharing more closely with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), while simultaneously increasing patient protections to avoid discrimination.

In terms of decreasing barriers to share, the proposed rule would allow generalized, one- time consents for HIPAA Privacy Rule purposes and re-disclosures in accordance with HIPAA. As a reminder, the HIPAA Privacy Rule allows sharing for treatment, payment, and healthcare operations.

In terms of strengthening patient protections, the new rule would give patients explicit rights to obtain an Accounting of Disclosures and expand restrictions on disclosures in civil, criminal, administrative, and legislative hearings.

This change has been long-awaited by Part 2 facilities and other in the health information exchange space, both of which are actively working to appropriately coordinate care for individuals who visit these facilities. This new rule is a large step in the right direction to prevent siloed behavioral health information and put in place practical rules to govern sharing of health information.

MiHIN & Native American Heritage Month

Health disparities among Native Americans are vast and persistent. Interoperability can help close that gap.

Michigan is home to 12 federally recognized tribes–with approximately 200,000 tribal members in total. Data show that Native American communities face inequity in health care and health status compared to other U.S. populations, including disproportionately higher rates of disease and shorter life expectancy.

The issue doesn’t end there – there are overarching challenges that further exacerbate the lack of access to care for American Indians, including the inability to accurately and seamlessly share digital health information, incomplete and fragmented data, and care processes that are siloed and not shared across boundaries. The bottom line: we must generate improved, more equitable health outcomes for Native populations in the state.

To account for the health disparity data gap, the Michigan Health Information Network (MiHIN), began working with the tribes in Michigan to establish culturally relevant, interoperable, health information exchange opportunities.

Under the leadership of Krystal Schramm, “Miskwa Mishiki Que – Red Turtle Woman,” descendant of Little River Band of Ottawa Indians Tribe, Senior Technical Business Analyst, the MiHIN team met one-on-one with tribes across the state to learn about each tribe’s respective patient populations, cultural needs, tribal clinics and clinical workflows and have been working with tribes to initiate utilization of the health information exchange dataflows to receive data for tribal patients from both tribal and non-tribal facilities.

Additionally, the MiHIN team has been collaborating closely with tribal clinic administrators and key tribal stakeholders to bridge the gap between tribal and non-trial entities in the State of Michigan, including the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, the Inter-Tribal Council of Michigan, MPHI, Indian Health Service, tribal government officials, the Michigan Tribal Health Directors’ Board, and the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society Michigan Chapter (HIMSS).

As a member of the Native community herself, Schramm was acutely aware that tribal populations have historically been underrepresented in public health data — and the resulting lack of support available when making decisions regarding tribal healthcare, both at the individual patient level and at clinic and system-wide levels.

Due to the fact that each of the 12 federally recognized tribes in Michigan are sovereign nations, the tribal healthcare system is inundated with piecemeal, disconnected and inconsistent data that leads to poor quality care, delays and no usable personal health record. By enabling the flow of data through the MiHIN network, health information can be shared quickly and seamlessly between systems, therefore establishing order and structure in the digital health ecosystem.

To date, eight of the 12 tribes and the Urban Indian Health Center have signed the necessary legal and technical agreements to join the statewide network of health information exchanging entities. By enabling the flow of data through the MiHIN network, health information can be shared quickly and seamlessly between systems, thereby increasing efficiency, improving patient care and safety and, ultimately, improving health equity amongst Native populations.

By nearly any measure, health care for Native Americans lags behind other U.S. populations. Facilitating a seamless interoperability between systems will provide patients and health professionals alike with real-time access to quality data. Increasing tribal representation in healthcare data will ultimately lead to improved health equity, outcomes, and patient satisfaction for tribal patients. More inclusive data equals better health equity.

To learn more about MiHIN or its work with Michigan’s Native American tribes, visit our website or contact Krystal Schramm at krystal.schramm@mihin.org.